M., a journey in a journey

I would have liked to come back and see me in your eyes again.

To see me again and to tell you everything I’ve been through, everything that overwhelmed me. To introduce you to my wife.

About the countless kilometers I have traveled, about the people I met, about the difficulties in the desert.

A long time has passed, or maybe it has never completely gone.

My journey began the day I never saw your eyes again, but they always remained, and still are, a part of me.

Jataba

I left in September 2011.

I left with a friend. I saw that many young people were leaving Gambia or I received stories of friends who had already left and managed to reach this distant land called Europe. In my land, there aren’t many chances for us young people: you can find temporary jobs with low wages, or the fate for most of us young people is to become a military man.

Even though I helped my father sell gas, my job didn’t allow me to support my family.

Therefore, driven by a great desire for a change in my family’s life and mine, I decided to leave for Libya, from where I could have reach Europe.

I knew it wasn’t going to be an easy journey, but I was so sure of my choice, so frustrated and tired about my life, that even in the darkest and hardest moments of my journey I never looked back, I never thought about going back.

So one morning I said goodbye to you, and to reassure you I told you I was only leaving for a few days, although in my heart I already knew from the beginning that we would not see each other for a long time.

I left with my backpack, some clothes and some food. I had no other documents than the electoral card, at least it had my name and a photo printed on it, because I had lost my identity card and I was waiting for a passport.

I had cut off the soles of my shoes and hidden some money inside them because, from what was said, at the borders, during checks, or along the journey, it could be very dangerous to have anything, especially money!

It was better to leave with the minimum necessary, even without a cell phone. I left with my friend from my hometown Kiang Jataba in Gambia and reached Senegal on a horse-drawn carriage.

Kayes

When we arrived in Senegal we took a bus and arrived at the border area with Mali, in the district of Kayes. Here the military stopped us, checked the bus and asked for our documents. Those who had them, had to pay a fairly high sum to go on; those who didn’t have them, had to pay double. Those who refused to pay or tried to escape were beaten and taken to prison. I paid double, because I didn’t have the documents, and they let us pass.

Bamako

Then we proceeded by bus to the capital of Mali, Bamako, where we were scammed by a fake bus agency. We wanted to rent one but, after collecting everyone’s money, they disappeared without accompanying us.

In Bamako my friend and I split up because he decided to take the bus to Burkina Faso since he had more money than me.

I, not having much money, together with other travel companions, we took mopeds to reach Mopti.

From Mopti to Gao

I, not having much money, together with other travel companions, we took mopeds to reach Mopti.

From Mopti to Gao to Libya it would have been faster instead of going to Burkina Faso and then Libya via Niger.

Only once I arrived in Mopti, I managed to get in touch with my family to tell them that I would not be back anytime soon.

Here I stayed three weeks with a young man I had just met, because I ran out of money. Together with him I got into debt with the “connection men” that are the migrant traffickers who hold the rent of the rooms (connection house) and they “help” you proceed along the way under payment. Therefore, to be able to pay them, we worked for 2 weeks as carpenters. We made some money and paid off our debts.

From the city of Mopti we waited to go to Gao because of the war. But the “connection man”, being aware of the developments, told us that the situation had calmed down and so, after a while, they drove us to Gao.

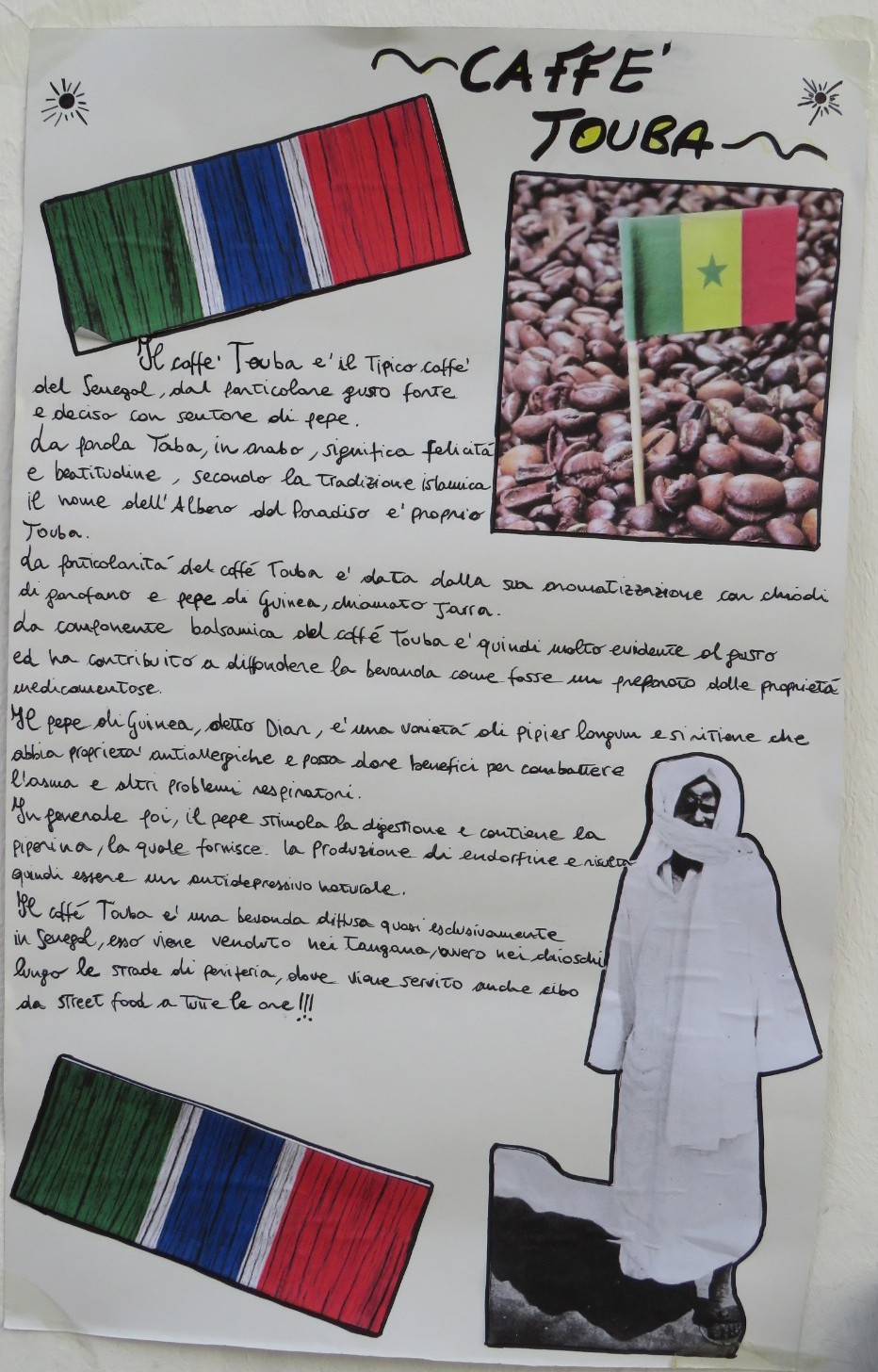

Gao is one of the cities in northern Mali under the control of the rebel Tuareg (Islamic fundamentalists).

We took a car to Algeria but during the journey we were stopped by a group of Tuareg who made us get off and raided everything. We gave them everything we had, that is, almost nothing. But they didn’t trust us because they thought we were “spies” and they took us to a prison in Gao. We stayed there for 3 months before their boss arrived, who was the only one who spoke English. My friend cried a lot and I got angry and banged my fists on the doors saying that we had to go, that we hadn’t done anything. They got angry and sometimes it happened that they hit us. Finally, one day, their boss arrived and we managed to make him understand that we were not spies but “mere migrants” on their way to Libya. Luckily, after a long discussion, he believed us and the next day we were released. From Gao they took us to a bus station nearby, were I met a local boy who helped the drivers find customers.

A group of Guerrilla Fighters

Niamey

The next day we took a car and drove to Niamey (capital of Niger) before being stopped by soldiers at the border between Niger and Mali. They let us pass because the driver explained our situation to them, that the rebels had taken everything from us and that we were on our journey.

When we arrived in Niamey, without money or cell phones, we stayed there for about 1 month. Here too, we looked for a job. The search was difficult but in the end we found a job as a bricklayers, they payed us and one night we bought some phone credit to call our families and tell them where we were, that we were fine. They calmed down and after a while my friend got some money from his parents. He had more money than me, so I suggested him to move on to Agadez without me but he refused and told me that he would wait for me to continue the journey together.

So I worked a little longer and then it was time to leave.

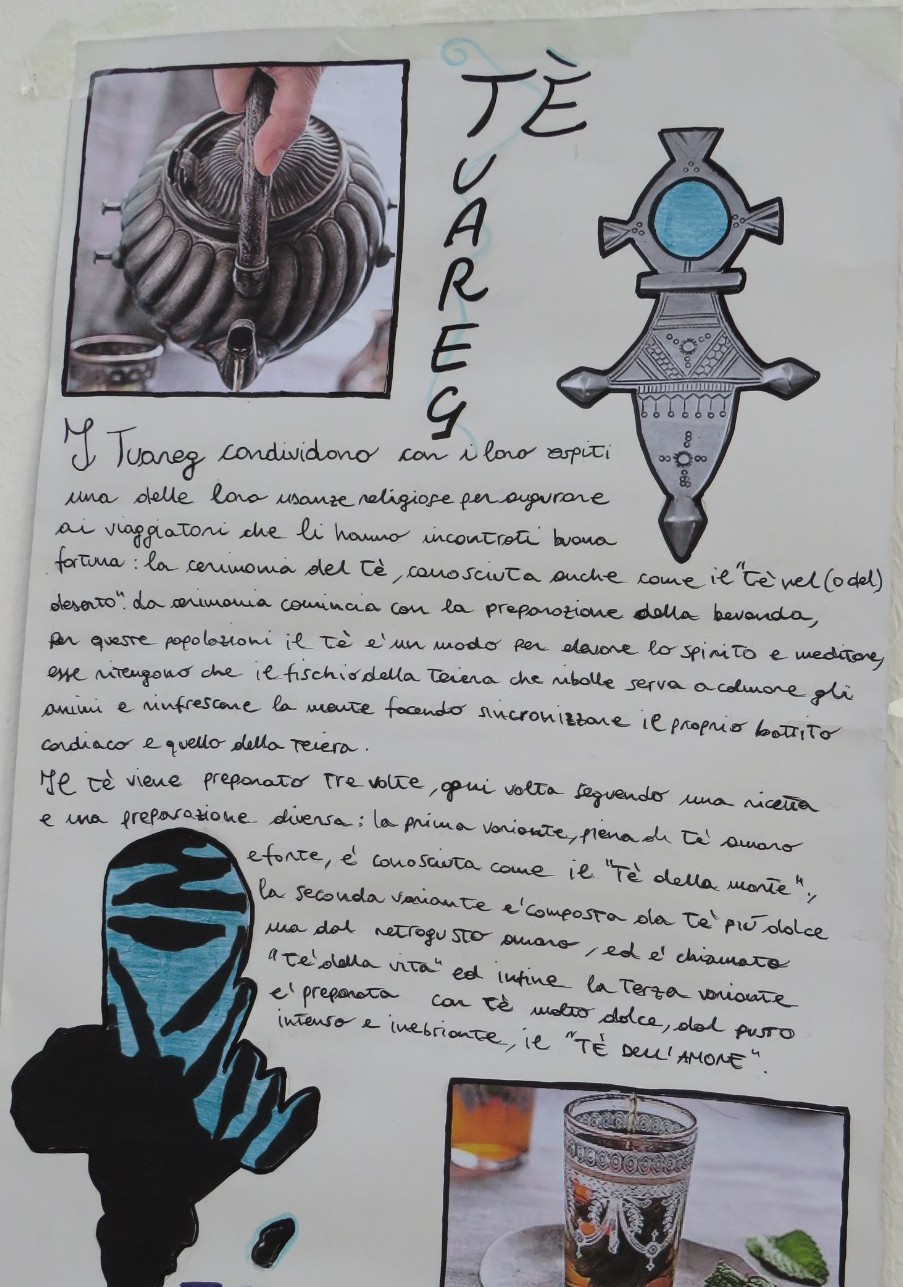

Agadez

So I left with other guys and after 3 days we reached Agadez, there I contacted my friend saying everything was ok, he told me he was leaving but in the end he decided to go back. From that moment on, we have never seen or heard from each other.

I stayed in Agadez for 1 month, staying in a “connection house”. In this city, since I have never managed to find a job, with the little money I had left, I stocked up at the bread and sauce market and I cooked during the night and resold on the street in the morning.

After I managed to make some money, I went to the bus station and paid for the bus ticket without paying the “connection man”.

In the evening we left for Arlit.

Aerial view of Agadez

From Niger to Algeria

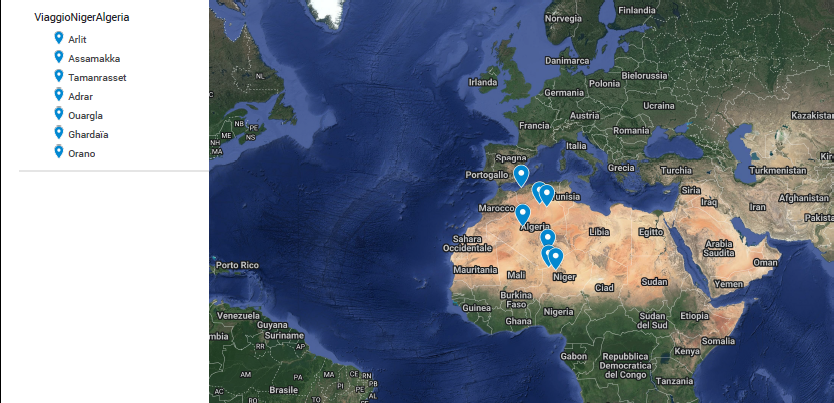

From Arlit we took a taxi to Assamakka and here we paid a connection man who accompanied us along the desert with 2 pickups (we were about ten people) to take us to Tamanrasset.

During the night, however, they left us off saying they would have come back but we didn’t see them anymore.

So we started walking in the desert until we saw some lights in the distance, it was the city of Tamanrasset. The next day we managed to get inside.

I stayed in Tamanrasset for 3 months because I found a job as a bricklayer again.

Once I collected some money, I went to Adrar and then to Ouargla, where I worked as a bricklayer and where we lived in a large abandoned factory.

After that, we took a bus to Ghardaia and then, through the city of Oran, to Maghnia.

Sreenshot of a Google map.

Nador

To survive, we went to look for food in the city of Nador. We knocked on the houses’ doors to beg for anything.

Often, the inhabitants helped us by giving us blankets, clothes and food. We find water in a spring of freezing water near our camp. We went there to get the water to heat to wash ourselves.

Melilla

The barrier separates Morocco from the two Spanish autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla, which are approximately 300 km apart. The two barriers surrounding the cities of Melilla and Ceuta along their entire perimeter were designed and built by Spain in the late 1990s to prevent illegal immigration. Millions of euros were allocated for this project by the European Union which cooperates with the Moroccan government to stem the phenomenon of migrations. You cannot have a clear idea of the amount of corruption and mafia behind the agreements between Europe and Morocco. The first one, has to defend somehow its reputation of an organization based on the “famous and steadfast” western modern principles of equality, peace, rights and democracy for everyone paying, nevertheless, much money and using the Moroccan military and police who, on the other hand, has to do the “dirty work” of pushing back so that they block, by any means and methods, the entry of immigrants into Spain and therefore in Europe. The Moroccan government, on the other hand, uses blackmail to receive more and more money from the UE. As a consequence, migrants find themselves in a limbo, at the mercy of the moods and needs of both parts. Human patches, puppets, in the hands of the great and powerful. If the Moroccan government, for example, needed more money, than it loosened the defenses of the barriers and let us pass more easily. But, if some of us managed to make the “leap” and fall into Spanish territory, the Spanish civil guard was still waiting for us, giving us back to the Moroccans. In any case, things remained unchanged for us: only blood, pain, death and despair

Mount Gourougou

We arrived at Mount Gourougou near Melilla, where migrants find shelter and try to overcome the barrier between Morocco and Spain. Whe have been there for about 2 years. The mountain has a very dry and rocky soil. Often, during the night raids that we organized toward the barrier, I saw many people who lost their lives by running like crazy (too fast) and tripping over the rocks that emerged from the ground, or during the regular roundups of the Moroccan police, to seek and “punish” us when we had attacked too much. When this happened, we fled altogether to the most inaccessible and high parts of the mountain, finding shelter even in very small holes inside the rocks.

Melilla

If you were lucky and made it through all three gratings you were in Melilla and you had to start running and not get caught by the Spanish civil guard who otherwise would have stopped, beat you and brought you back over the barrier to the Moroccan police. But if, after all this, you managed to escape from the civil guard, you had passed the level. You had won. The streets of Melilla were filled with screaming migrants, joyful but exhausted because they had made it. They had arrived in “Welcoming Europe”. They went to the reception center in Melilla where they could apply for asylum. I have never been among these lucky ones, I have tried many times to enter. One day I managed to climb over all three barriers but trying to get off the third one, the civil guard who was on the ground started yelling at me “descendez! descendez!” and I replied that no, I didn’t want to get off. Then he pointed the gun on me. I did not think he would have fired and instead the shot went off. He first shot me in the neck, always screaming “descendez!” but I remained up there sore and dangling, holding with only one arm clinging to the net. So he reloaded the rifle and hit me in the gut. At that point I was no longer able to hold on to the grating and I let myself go from 7 meters high. I fell to the ground, one of them stomped all over me, I managed to escape between his legs and then I started running with the last strength I had, but I had too much pain everywhere. As I ran, the zip of my sweatshirt opened and one sleeve came off. Two of the 5 Spanish guards who were following me managed to stop me pulling my sleeve that had slipped off and threw me down on my back. They pinned me by holding my knees together on the rocky ground and pinning my hands. As if that weren’t enough, one of them took a brass knuckle out of his pocket and started beating me on my head which started to bleed. Then they dragged me over the barrier leaving me to the Moroccan policemen who beat me repeatedly with sticks until my leg broke.

From Melilla to Lybia

Then they took me to the border between Morocco and Algeria in a Country near Oujda. There I found Shelter in the porch of an abandoned house and the villagers helped me by bringing me medicines and healing the wounds I had all over my body.

My leg hurt a lot. But I resisted. I stayed there for some time, I remember it was very cold and I often lit the fire to warm myself. When I felt a little better, using two sticks to help myself I started walking again towards Mount Gourougou. After a day of travel I arrived at the mountain but given my health conditions I could not go up its slopes. So, seeing some guys passing by, I asked them to tell my fellow Gambians to help me go up the mountain. They came to help me shortly after and I remember they were very amazed to see me and happy that I was still alive. When I arrived at our camp, my knee was very swollen and I couldn’t walk for a month. Even the police, when they did their usual roundups, found me alone and did nothing but mock me for the fact that I was still alive and that I didn’t go back to my country. If you were sick or injured there was no problem for them, they would live you alone, since you could not run and climb the barriers, so you would not have created any problems. The problems only arose if you tried to cross the barrier as Europe paid the Moroccan police to guard the border. I remember very well the words of the Moroccan agent who found me at the camp: ”If you want to stay here there is no problem, if you go there you make us look bad because it seems that we are not working”. After my return to mount Gourougou and after spending a month stuck in the camp due to my broken knee, another 5 months have passed. In the meantime we have tried many other attacks to enter Melilla, but by now I was tired of the situation. It was very hard to go on surviving in those conditions and very dangerous to try to cross the barrier.

So I decided to leave the mountain and go back, to go to Libya. So I retraced the route in reverse: I went by bus to Oujda, then Maghnia, Orano, Ghardaia and Ouargla. From Ouargla by car towards In Amenas, Deb Deb, Ghadames up to Tripoli.

Google map screenshot.

Tripoli

When I arrived in Tripoli, I immediately looked for a job to be able to pay for the trip by sea. I was there for a month and it was very difficult and dangerous because there was a war between the Libyan military and the rebels.

I often found myself in dangerous situations between the two sides. You left the house but you did not know if you would come back. There I lived in a “connection house” too.

One night they decided that we would live, they told us that we would live in 75 people, instead in the end we were 120 people. They picked us up in the city with their cars, called us by name and took us to the beach. Here we inflated the dinghy. The traffickers are smart, they didn’t come with us. They look for migrants who can drive the rubber dinghy and they teach us how to use a GPS.

I paid “only” 700 euros because my stay in the city was quite long and they knew me “well”. Many, on the other hand, paid up to 100 euros.

We then left at night and the following evening the boat began to deflate.

My first journey can be said to have ended that morning when the Italian coast guard, after having sighted and rescued us, left us at the port of Salerno.

Salerno

We arrived in Salerno in September 2014, they visited us, we ate and then they called us by name and divided us in different buses.

Bologna

To my family,

to my brothers,

to the friends left at home and to all those scattered around the

Great Earth.

To all traveling people,

to those who have already arrived and those who are still

traveling,

to every migrant of the past and present,

of any will and any circumstances,

to the trip,

to the freedom of every man,

to the land without barriers.

Bologna / a journey within a journey

My bus arrived in Bologna, at the reception center in via Mattei. When I arrived I didn’t know either the language nor the city. I spent most of the day around, where I met many people and other guys who, like me, had arrived after the long journey. However, I remember well that one day, turning around the Sant’Orsola area, I saw many people in running gear who were all going in one direction. Intrigued, since I am a sports guy, I followed them and found myself in front of a large park called Giardini Margherita.

I was immediately impressed by the green of the meadows and trees, by the pond, by the many people who frequented it. It seemed to me like a happy island. This park is the place where I met for the first time the girl who was going to become my wife.

I was in via Mattei for a month then they moved us to a hotel where we stayed for a week. Then they took us to a community for minors where I stayed for 1 year and seven months. In the meantime, I studied for the “terza media” and graduated from CEFAL as an electrician. They found me an internship as a warehouse worker but at a certain point my stay in the community had to come to an end because I was now of age. So I went to a community where a small rent had to be paid, but the internship ended and the job did not go on. So I was not able to pay the rent anymore and I left the community. The next day, along with other guys, I had a problem with the police. They raided a park during a party with a lot of people. They took people at random and without motivation. I was one of those.

Having received the order to stay away from Bologna for a certain period, I went to Sasso Marconi where there was a friend of Sonko’s (a dear friend with whom I spent the period in the Gourougou mountains and with whom we took part of the road to Libya and found ourselves in Bologna) who hosted us for a while. After some time we returned to Bologna, sleeping in a park in Casalecchio where they evacuated us and then through friends I found a place to sleep at an association in Bologna. Here too, however, it was a temporary situation and following other friends we went to an abandoned farmhouse in via Stalingrado. After that, my wife managed to find a room to rent. Later, we learned that the place in via Stalingrado had been cleared and months later, it had burned down.

With big efforts, over the years, I have managed to find various jobs with employment Agencies.

Bologna / The Wedding

We met in the summer, during a festival of Cultures and Music from the world.

I remember that every night I met there with my friends with the home to see her again and talk to her.

Since that period, since 2014 we have always remained “close”, she always helped me in whatever situation I was and always looked for solutions for me.

With her I started a musical project, we do black music dj-sets (hip hop-reggae-dance hall) also involving other people who want to sing. We have played in several occasions and parties where beautiful situations have always been created.

Bologna_2022

Starting from the traumatic experiences of those who suffered in Monte Sole to listen to the close memories and distant tales that migrants bring with them.

Go to Anna Rosa’s account and explore her story.