Physical abuse in the form of beatings or even attempted rape was also present: “There was a lot of torture, with threats and all, that you’re all going to die now, we’re going to cut off your food and make you eat snakes, etc.”. “They were looking for a reason to hit us, to assault us with unspeakable curses, and finally to lock us up, starved, in the dungeon in the monastery.”

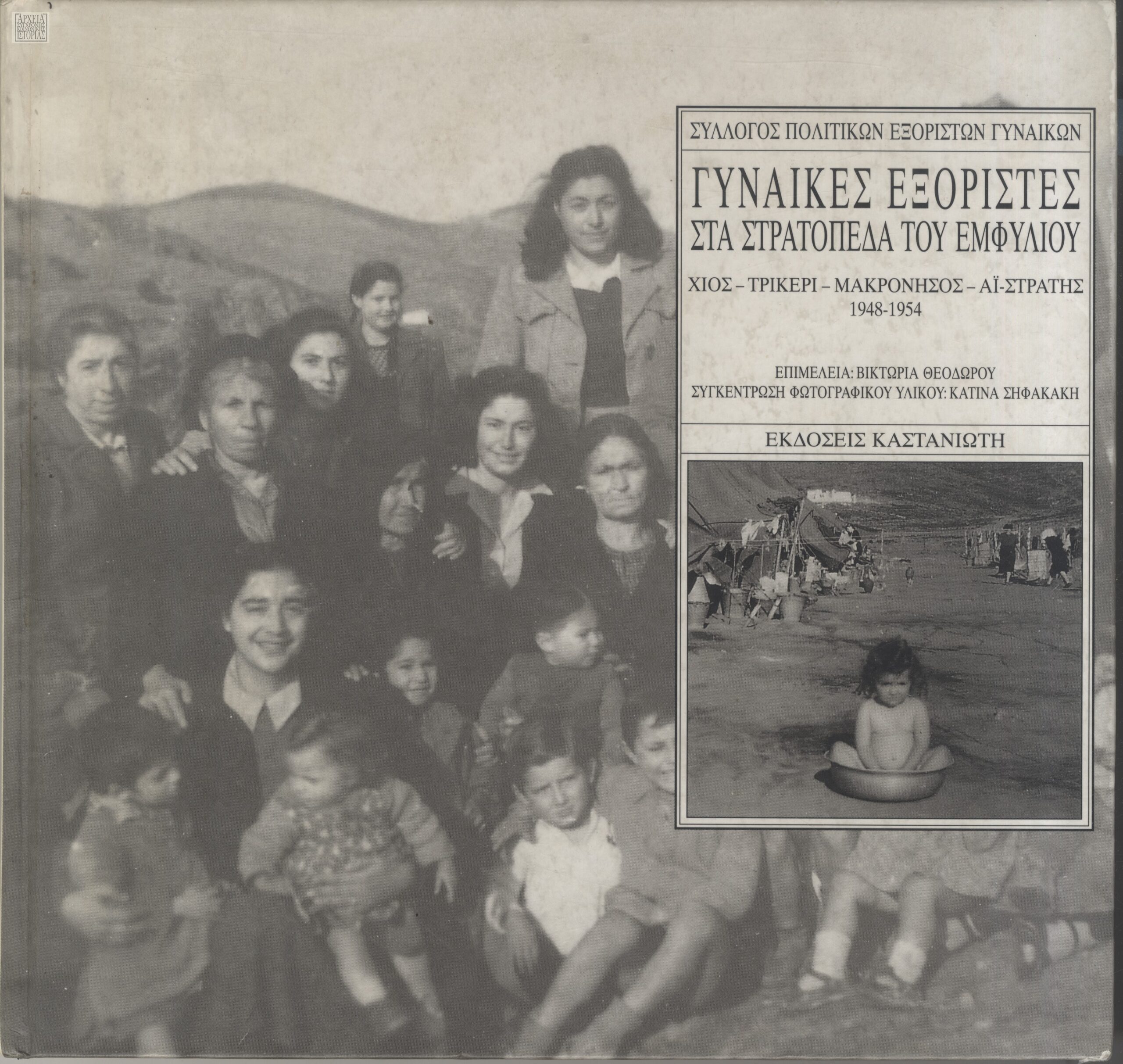

Living in confined spaces: Trikeri, female concentration camp

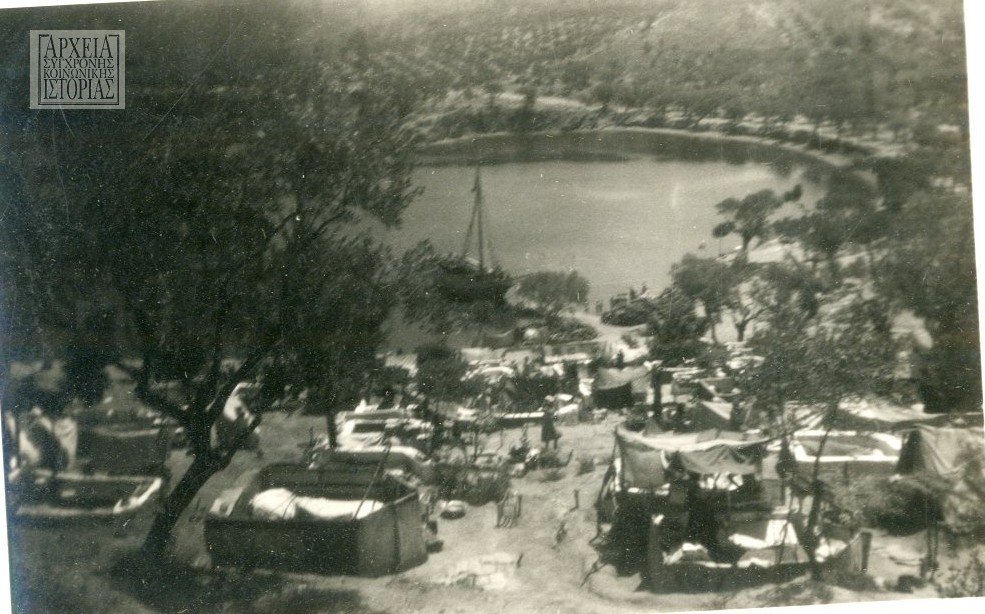

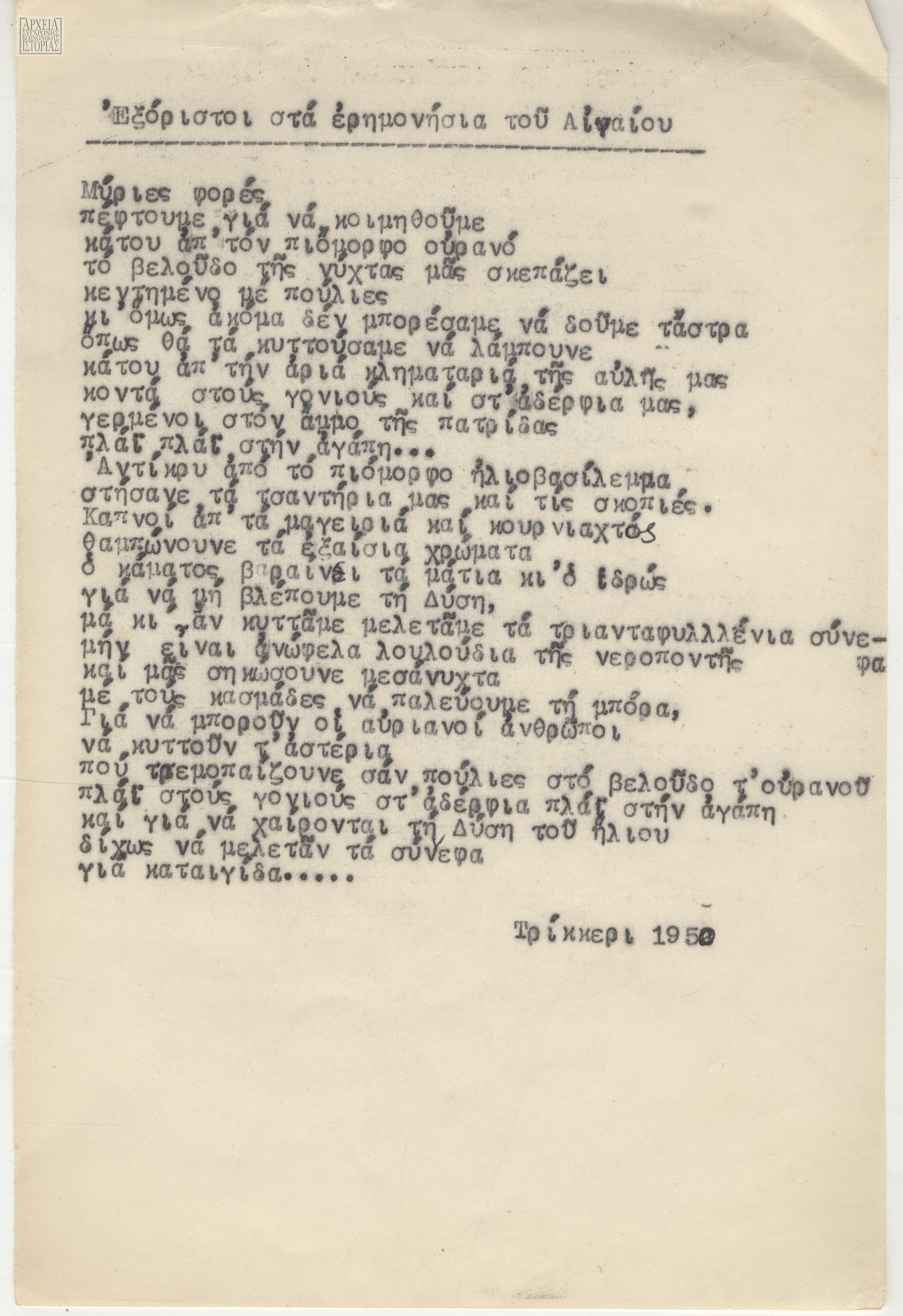

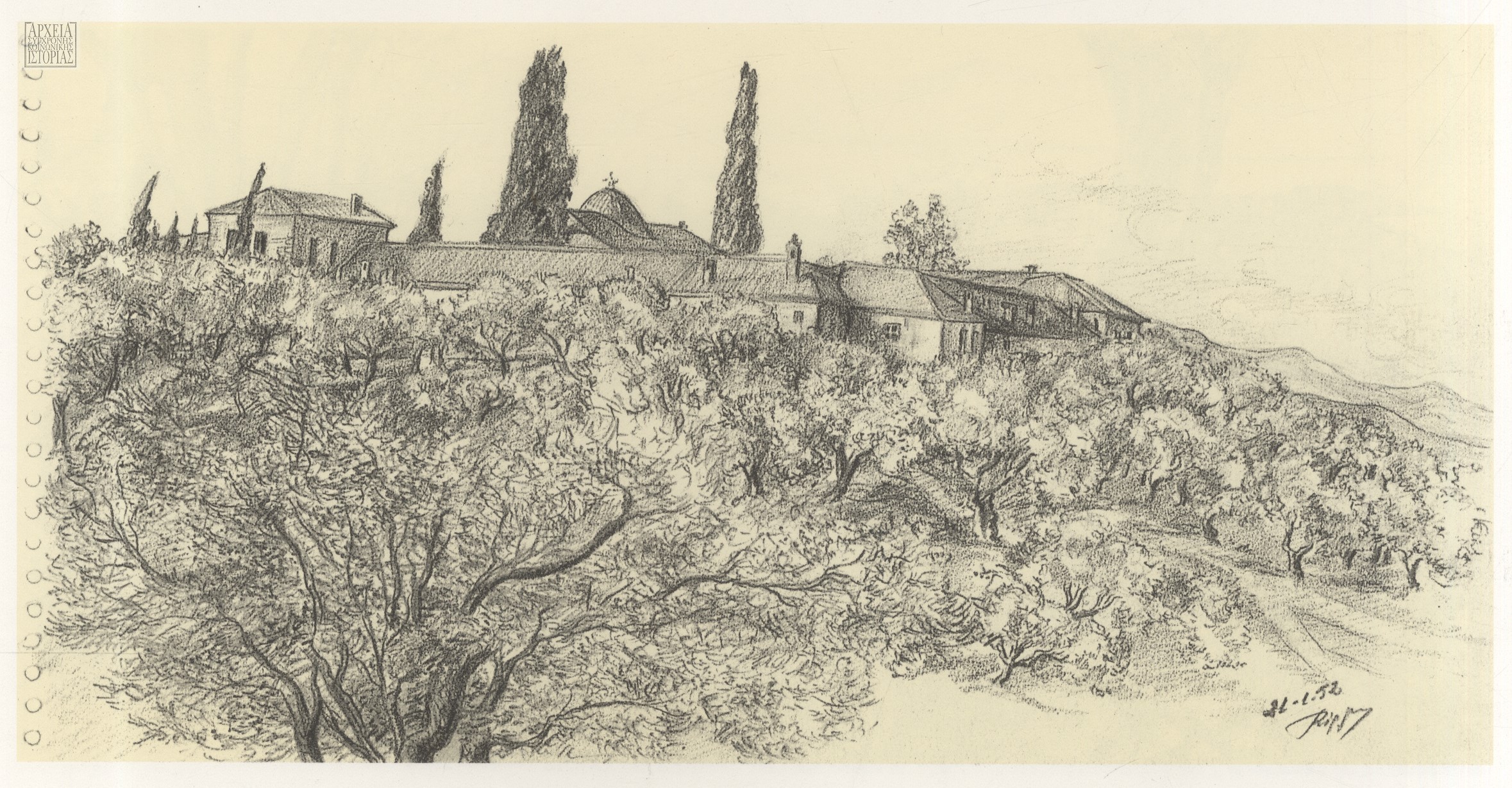

Trikeri is a tiny island in the Pagasetic Gulf in the north of Greece, isolated and inaccessible due to its geographical position – an excellent site for the establishment of a concentration camp. From 1949 to 1953, nearly 5,000 women were exiled to this deserted island.

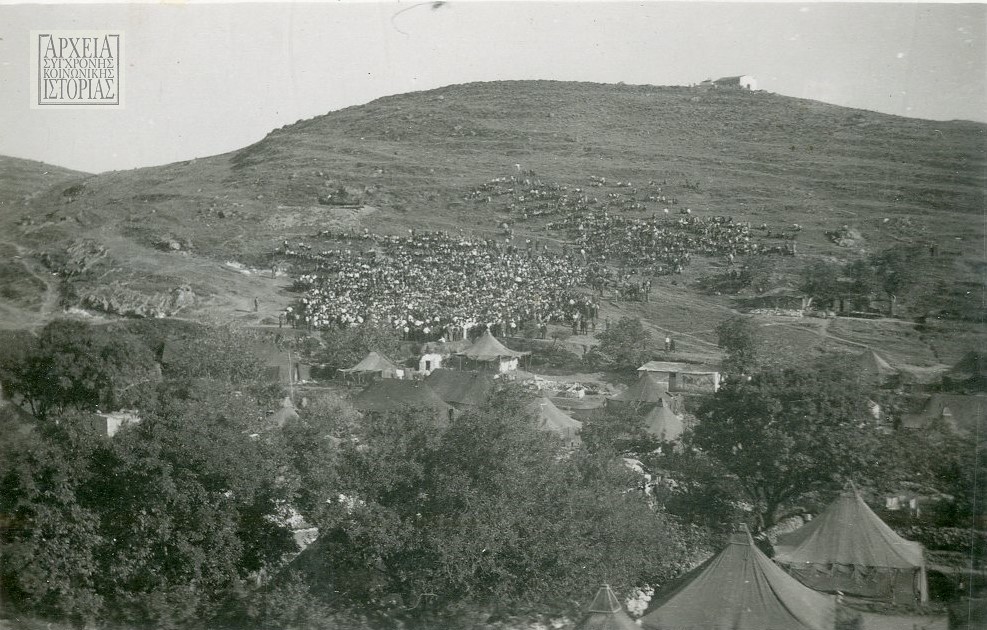

Camp and harbour

When the women, many carrying babies, landed on Trikeri, they were pleasantly surprised by the stunning views and the green landscape. Nevertheless, they quickly realized that they would be living in conditions of extreme deprivation and constant physical and psychological pain. The exiles in Trikeri faced extreme hardship, ranging from the lack of water and medical treatment to malnutrition and forced labour, all while subject to military discipline and constant pressure to sign statements of repentance.

The irrational camp regulations imposed unnecessary hardships on them, such as by requiring them to carry all the food supplies and building material from the port to their tents. They were forced to make circles around the island, rather than being allowed to take the most direct route, and had to carry all the provisions themselves – firewood, cement, and bricks and mortar for 5,000 women – going uphill. “We hadn’t the courage to see the nature of April, nor the enchanting sea that we longed for. Because our heads were bent towards the earth and our minds were on how to climb uphill without stumbling on the rocks. Since then, the women called it ‘Calvary’. […] Nor did we have the freedom to wash ourselves in the sea, because we felt the eyes of the guards everywhere”.

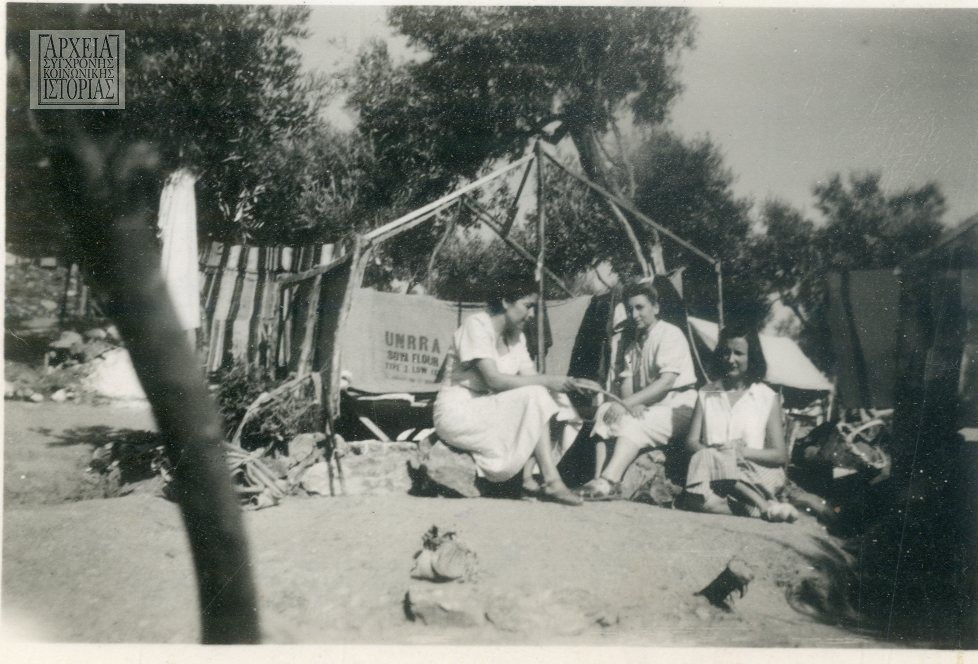

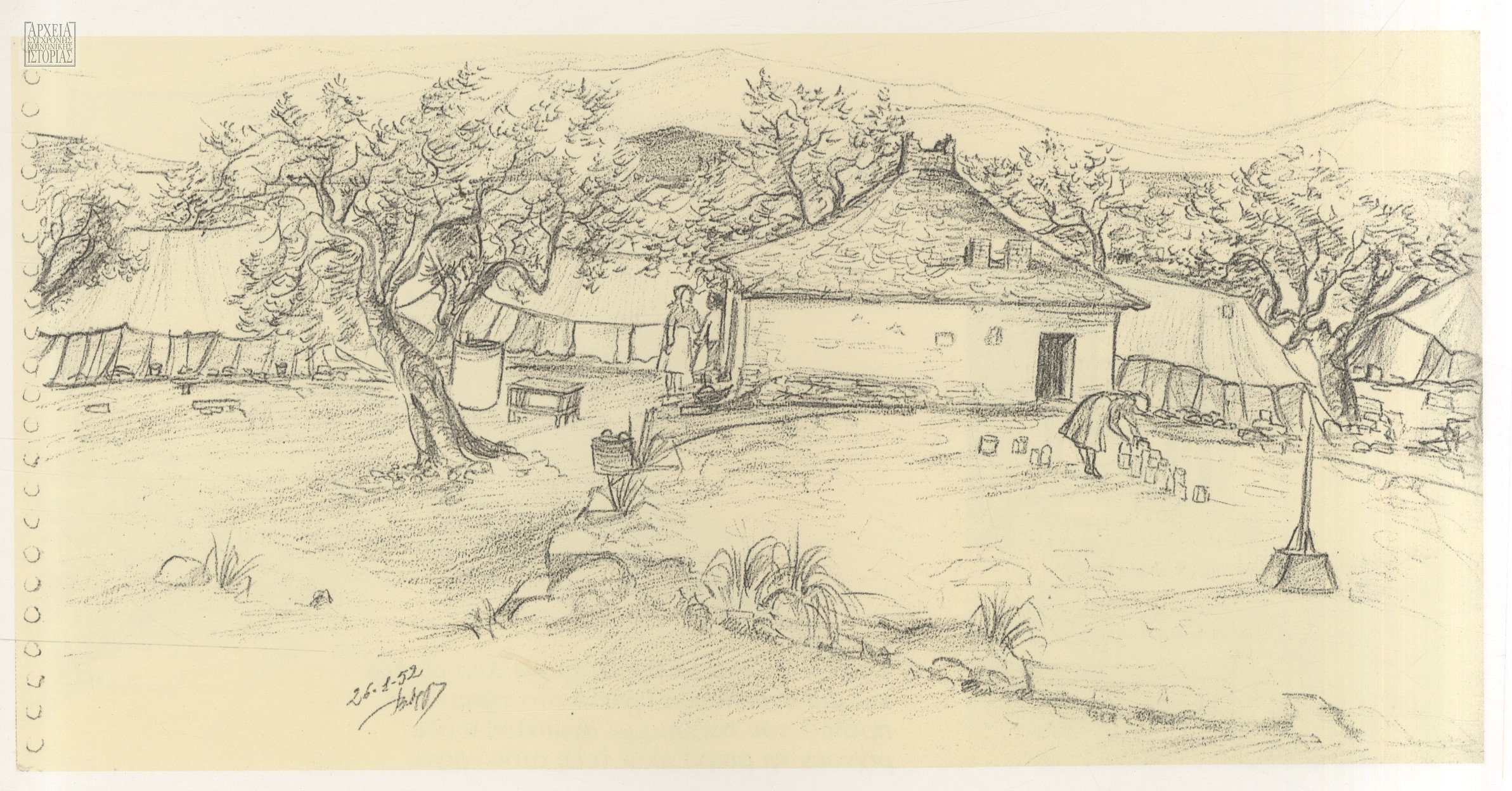

Living in tents

“Our life in Trikeri was horrible. We stayed outside in tents. In the summer, we suffered from the heat. And, of course, there were terrible flies. It was terribly hot, and the canvas absorbed the heat, and we couldn’t do much about it. When the first rains started […] and they blew away our tents, we were forced to request that they let us rebuild our tents up on the hill, close to the monastery, where it was more sheltered from the wind. So, we did that, and they came a couple of times and destroyed these tents, forcing us to rebuild them again each time. And they beat us around, and made us sleep in the mud, even with the children, to force us to give in and sign statements”. After 8 p.m., they were not permitted to have any light in their tents and all movement was strictly prohibited.

Physical abuse

Diseases

Diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, typhus, dysentery, and scabies frequently ripped through the camp, while healthcare for the women and children was non-existent: “Paraskevi, a young exiled woman, as soon as she arrived in Trikeri, after the sufferings, she started to grow pale and melt. Later, she bled continuously in her tent in front of the terrified women. Shortly, exhausted as she was, and desperate, she signed a statement of repentance and left on a stretcher. Did she live? […] Vagelitsa, a small 18-year-old village girl, died of tuberculosis a few days after she arrived at the camp. She was buried there as an animal, but I must not forget her”. During these terrible outbreaks of disease, the administration did not provide any rice, sugar, lemons, or even medicine. The camp doctor kept the medicines provided by the Red Cross and sold them to the exiles at a high price.

Children in Trikeri

The presence of the children was a source of both comfort and torture for their mothers. The Red Cross did not recognize the children as prisoners, so there were no food supplies for them.

The growing number of children – 224 in total – were fed with food provided by their mothers. Τhe women always made sure to take food for the children from the large cauldron of the breadline, keeping this a secret from the administration, thus reducing their own portions.

Women gave birth in the camp and watched their children fall ill or die: “In September 1949, a woman gave birth to twins on the ground. One baby died after two days and the other was christened Eleftheria, which means freedom in Greek. She, too, died a week later”.

Interview of Xristos Trikalinos, child in Trikeri

Because soap and water were so scarce and expensive, the children were soiled, tattered, and pale, “shadows like child ghosts. For these children, above all, some mothers made a statement and left the cursed island”.

Interview of Sotiris Baratsis, child in Trikeri

The abduction of their children was another tactic used to press them to sign. Children were considered national property, and the role of the nation in their upbringing was, therefore, vital to save them: “Your children belong to Greece. Anyone who wants her child must first become Greek”.

Interview of Lefteris Tsakiris, child in Trikeri

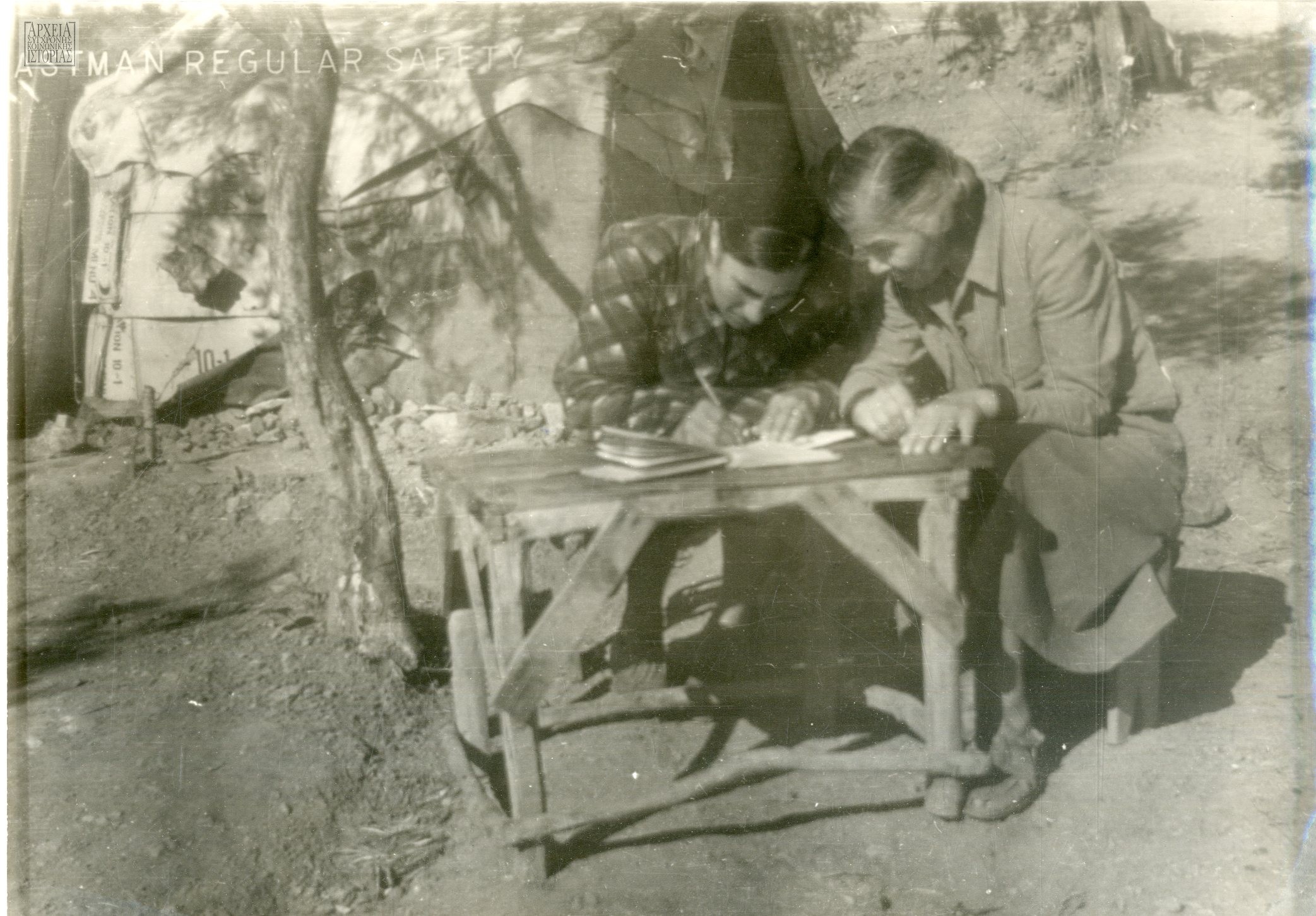

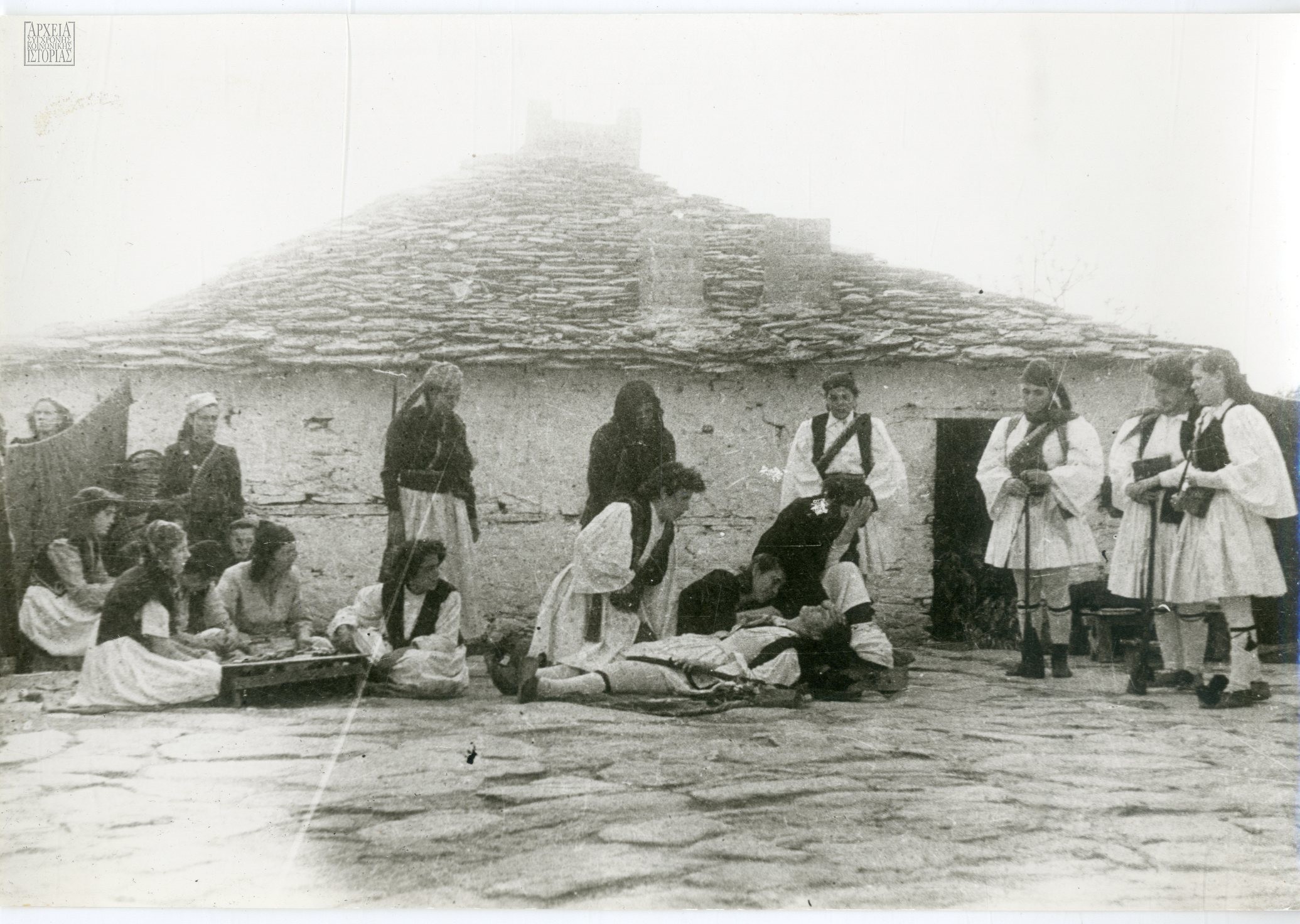

They taught classes for the children and also managed to build a day nursery, where they entertained children while their mothers were busy with chores. There the children did exercise, played, sang, and learned to write in the sand: “There were 182 children in the day nursery. One Sunday, we all happily went up to the plateau where they would perform theatre. There was a great emotion. They performed Little Red Riding Hood for us. […] How hard it was to do all this, and how difficult it was to discipline those little savages!”.

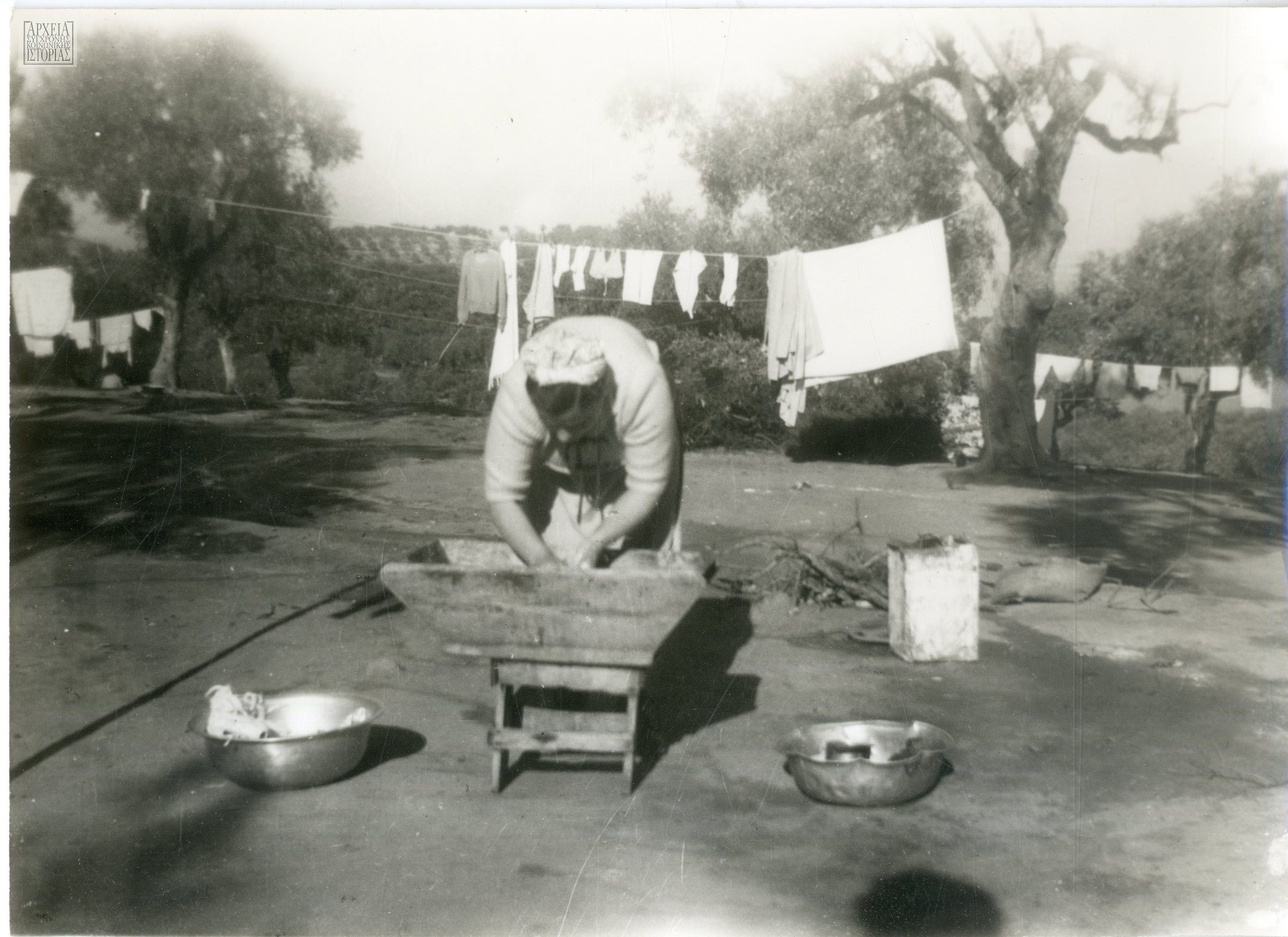

Searching for water

The lack of water was also stated to be a major problem. The men who were exiled to Trikeri before it was transformed into a female camp had constructed four wells. However, only one worked, and the water was very muddy. The women had to rise very early, form never-ending queues, and wait for hours to have some water for their daily needs, in addition to queuing in long breadlines under the military system. They described their daily lives as a constant queue: “We got up secretly before dawn to go to the wells in the hope that we would be the first ones. And yet again, under the trees, we found women awake, pale and wild, waiting for the water”.

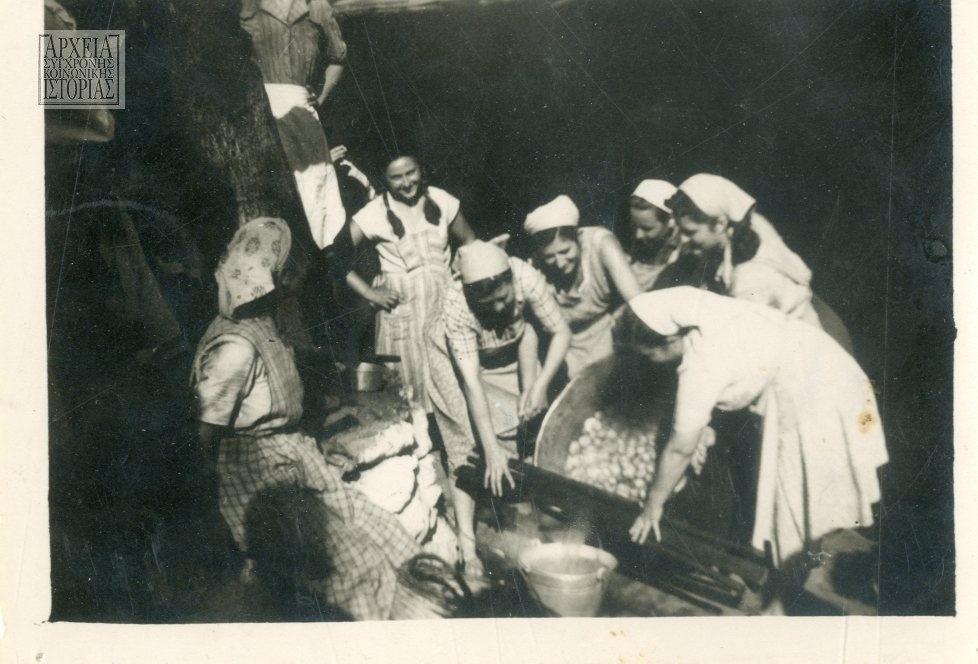

Searching for food

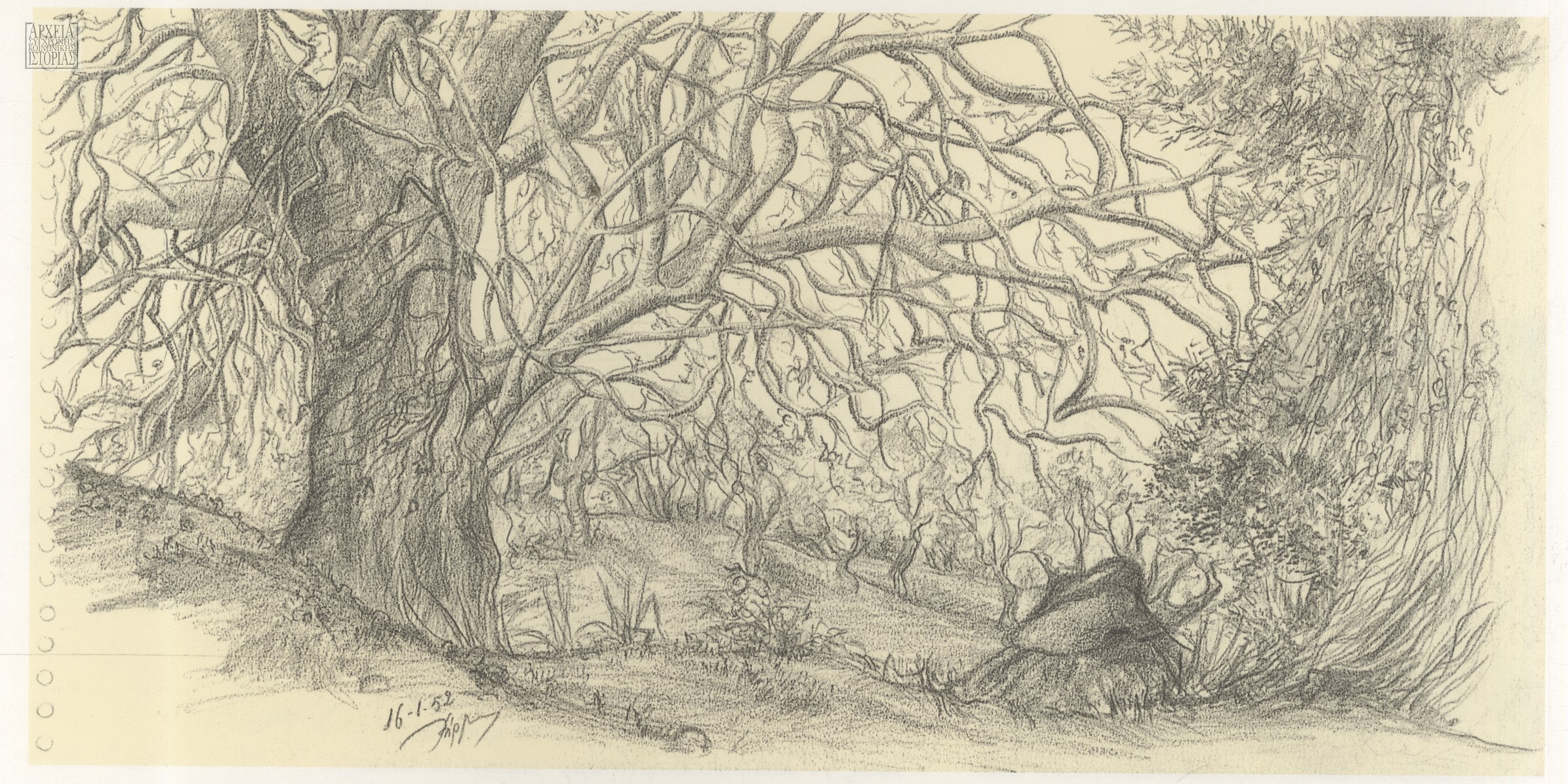

A starvation diet was imposed, with insufficient food rations; they normally ate beans and chickpeas with a slice of bread. But the women found ways of surviving: “Fortunately for us, there were a lot of olive trees around there and we would gather them and soak them in seawater brine […] Also, there were wild mushrooms growing around the bases of the olive trees and we would pick those. I would say to the children, ‘Come on, you are going to eat liver’. And those few olives and mushrooms helped us get through the hunger”.

Smiling

In their photographic testimony – pictures they took of themselves to send to relatives – the women are smiling, giving a misleading sense of happiness in order to reassure their families that they are well.

Additionally, the guards – besides censoring the letters they sent to their families – frequently kept or even burnt the letters that their families sent them as a punishment: “And then we saw the fires burning our letters. Thousands of letters, cards and books were burned last night”. The guards read the letters the women received, and when news arrived about the death of a family member, they would save these letters for last, reading them in front of the poor mother, sister, or wife. In the letters that they were allowed to send to their families once a week, they could only write that they were well due to censorship.

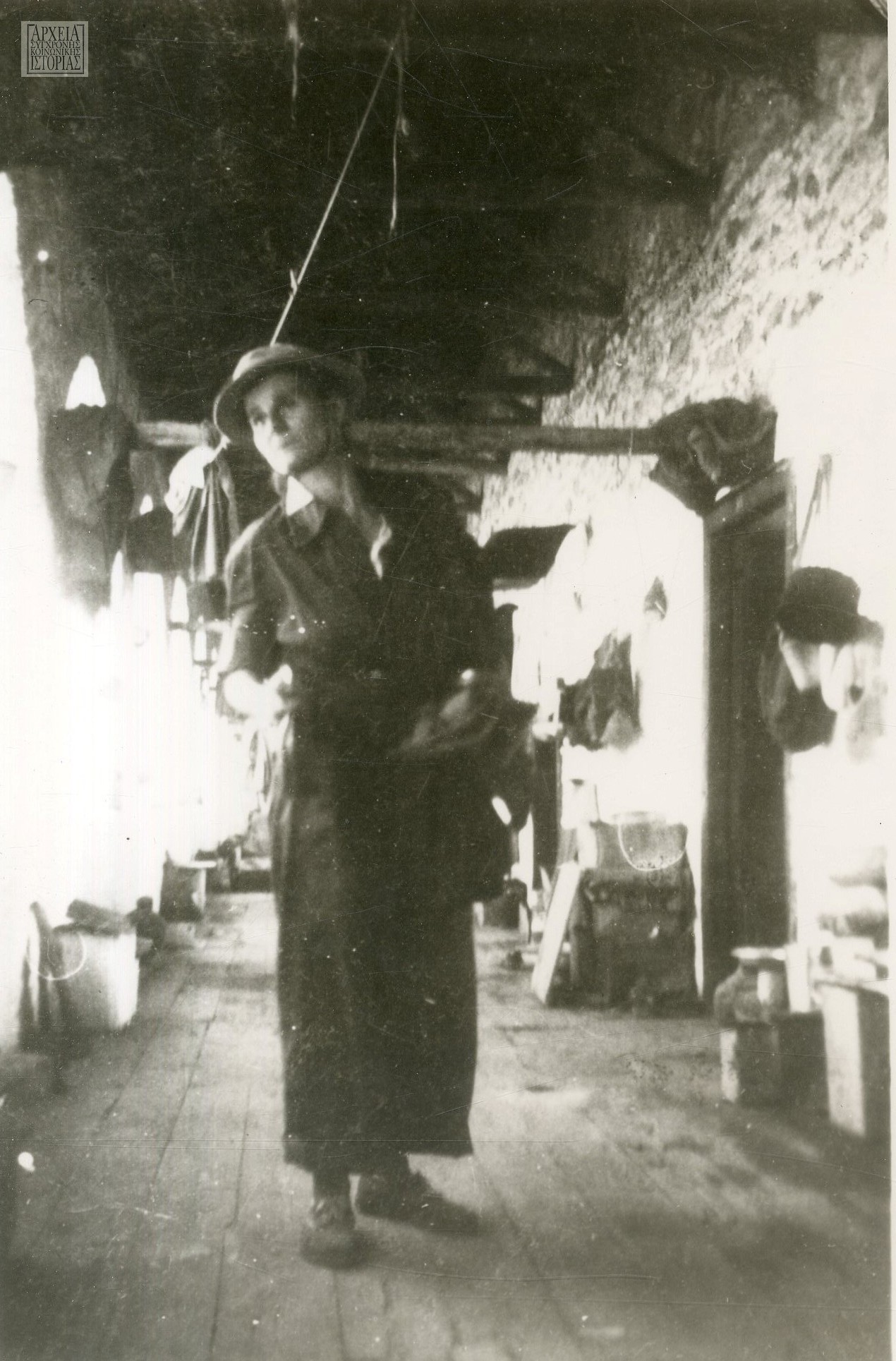

A hive of work and education

“Trikeri became a hive of work and education, a peculiar nunnery, unique in the world”. The women formed committees for the unloading and carrying of supplies, retrieving water from wells, carpentry, cleaning, cooking, food distribution, classes, recreation, and childcare, disencumbering the elderly women and the children. “Here was the shoe store where Kalliroi made sandals and patched shoes. Below, the Pontic Greeks made mattresses, quilts, and pillows. Next to them, Foto made tables and beds for the children. The tinsmiths made gas cans from cans. On the left was Evangelia, who remade Red Cross clothes. To the right was Katerina’s studio”. In their “free time” they did crafts, knitting, and embroidery, and even volleyball, basketball, and pantomime: “We cut the olive wood and made spoons and other small tools. We embroidered with shells and made various ornaments, necklaces, and toys for the children”.

Classes

In the camp, in addition to the children, there were 230 illiterate women, 380 who only knew how to write their names, and 52 teachers, among them the prominent educationalist and prewar feminist Rosa Imvrioti and the famous professor, educationalist, and art historian Liza Kotou. Secret classes were held daily all over the camp, while Imvrioti gave lectures on fine arts, history, folklore, and hygiene. The teachers prepared high school age girls for university. “Those middle-aged women who had never had the chance to see or hear a teacher, they learnt their first letters here. And those who wanted to learn a foreign language, they succeeded here in the camp. There were teachers to teach you accounting, shorthand, drawing, cutting, sewing, whatever job you wanted to make your living tomorrow”.

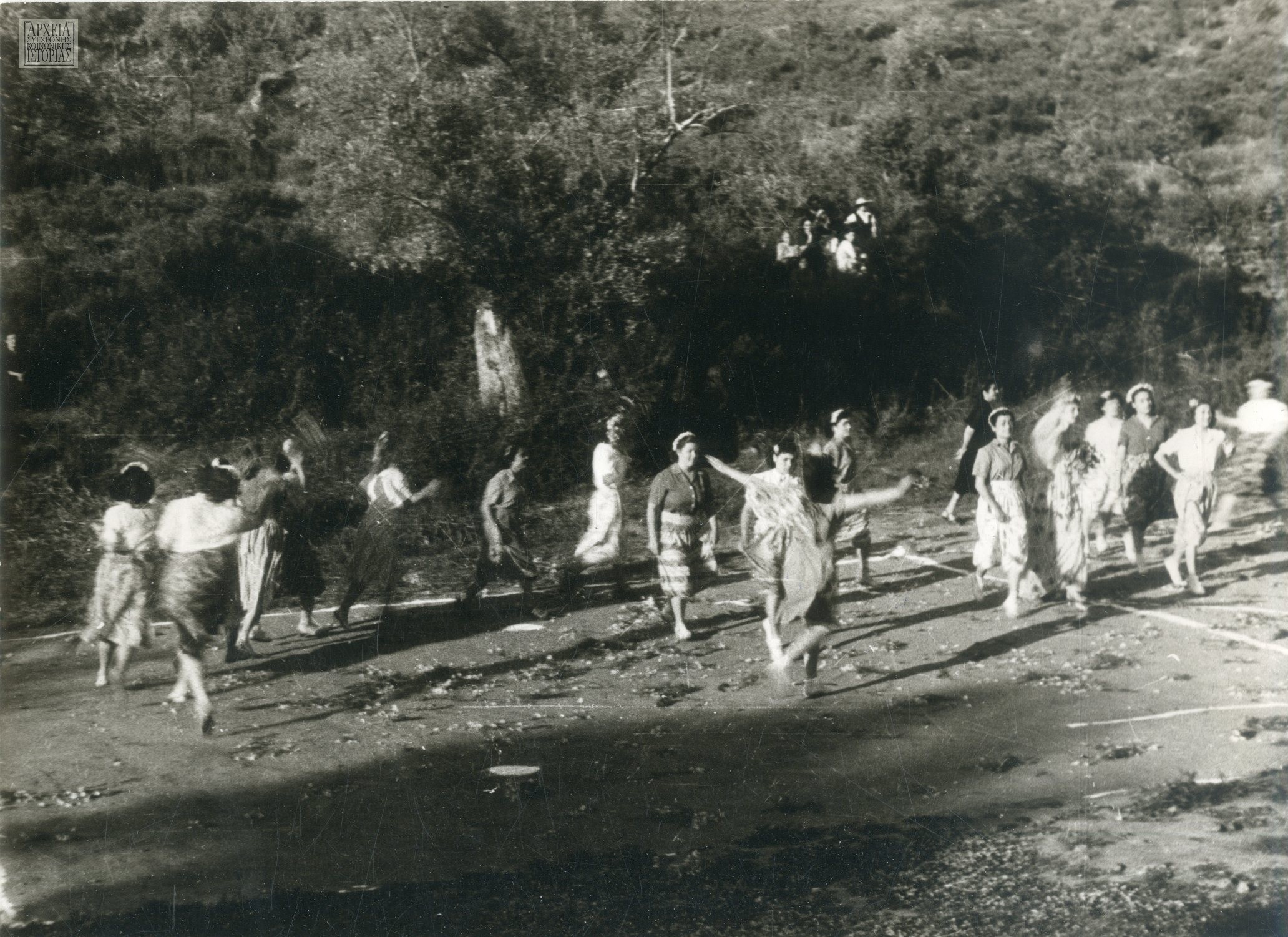

Dance and music

Various measures of resistance were collectively agreed upon and used for mutual encouragement. These included lessons, plays, and singing: “There I learnt dances from all parts of Greece, and songs from all over. We would teach each other our native songs and dances. I danced, I was in plays, I joked my way through”.

“For the very old women, we would go stand outside their tents, where they sat down speechless, and sing to them. This was our help, no greater than that which they were giving us with their courage and patience when they heard that one of their children was dead”.

Strategies of survival and resistance

The women adopted strategies of resistance that differed significantly from those of men, such as colour – their dresses were a river of colours. There was a tacit agreement not to wear black clothes, even though almost every woman in the camp could have done so on the grounds of mourning. Every day, they received news of executions: “Many women in mourning wanted to withdraw to remember their beloved dead unceasingly. They were melancholy, they wanted to commit suicide, that’s why we never left them alone”.

Cleaning their bodies, their clothes, and taking care of their appearance was another strategy of survival and resistance. The women said farewell to those sentenced to death by “giving them a souvenir or some money and washing and combing their hair so that they would depart beautiful and optimist”.

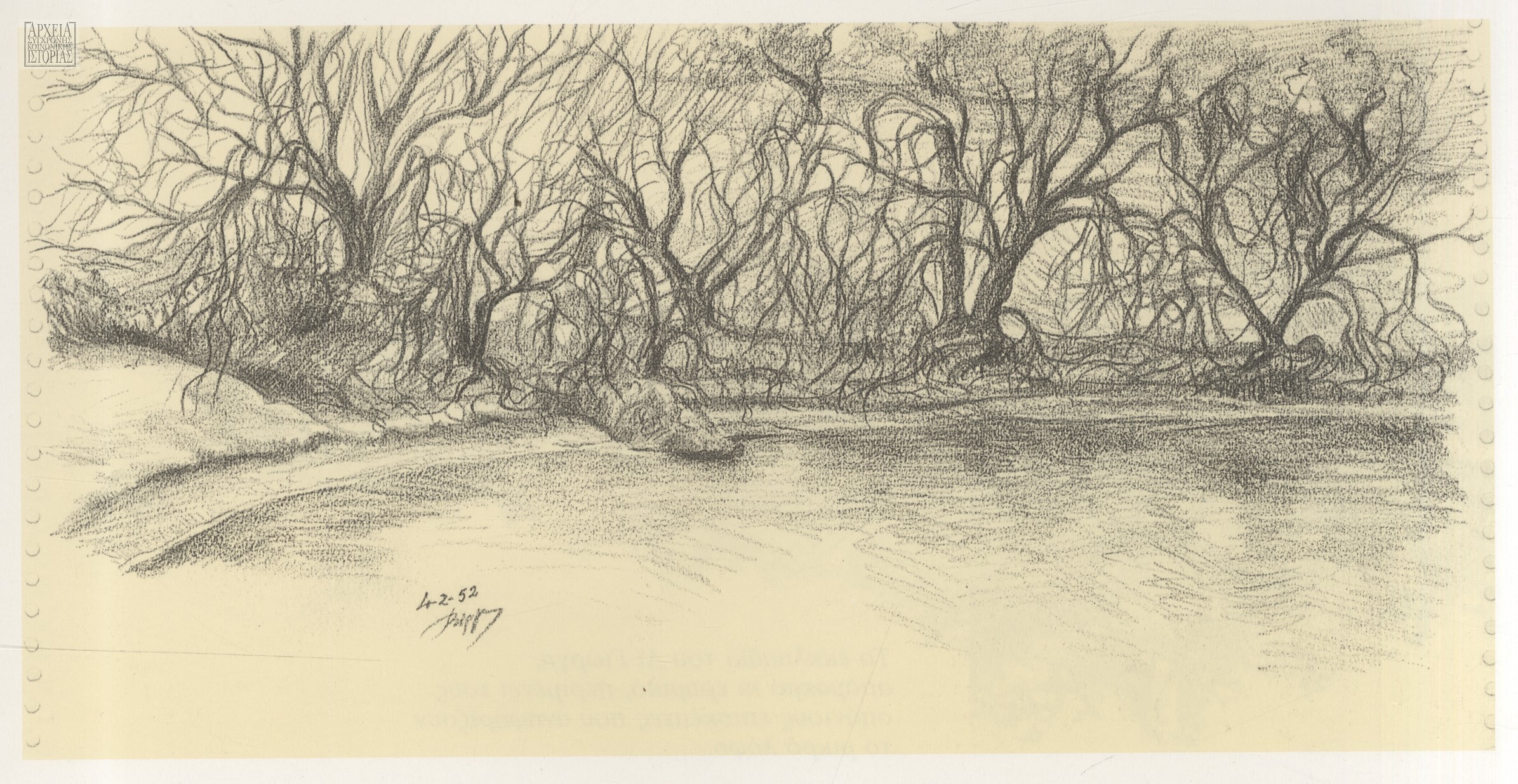

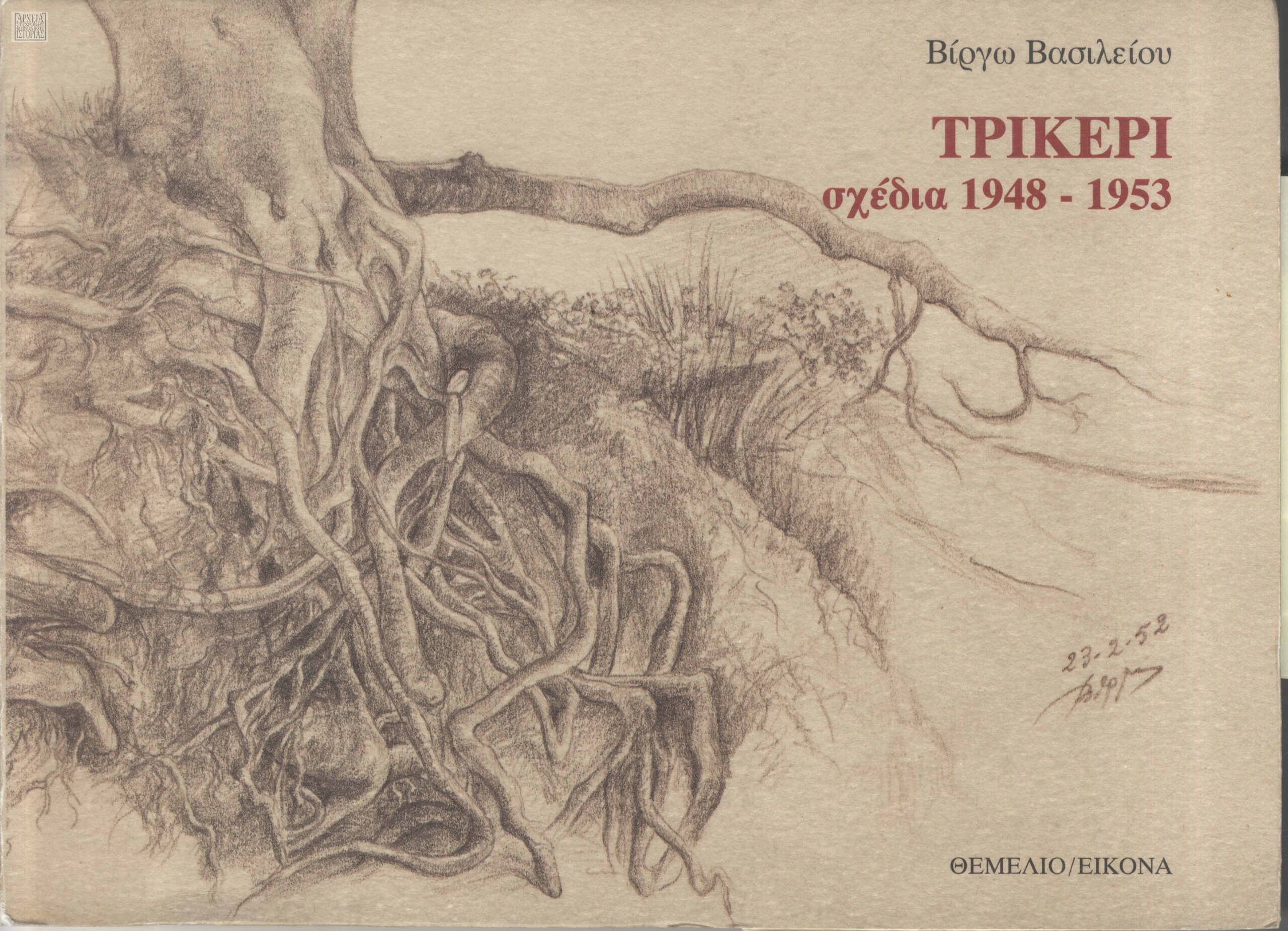

Art in Trikeri

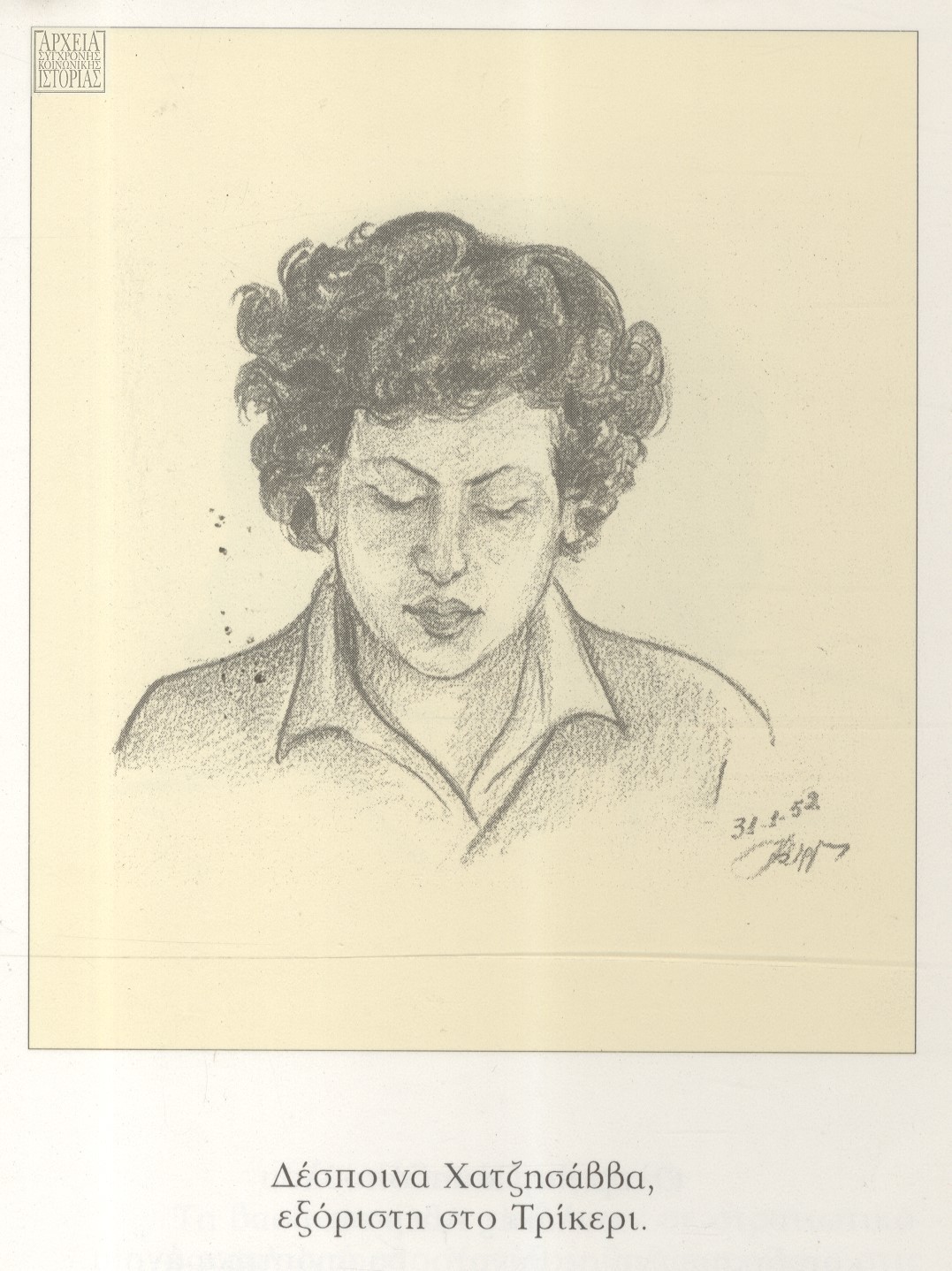

Drawing of Despina Hadjisavva, exiled in Trikeri, made by her co-exile painter Virgo Vasileiou

The burried notebooks

Remembering their story

In 1991, the Association of Women Political Exiles sought permission from the religious authorities to place an honorary plaque in the monastery on the island of Trikeri. However, the bishop proclaimed that it was time to forgive past discord, in order to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past in the future. Finally, in 2017, the Federation of the Greek Women placed the honorary plaque in the monastery.

Visiting Trikeri again

The ex exiled women visited Trikeri again in 2000